Guidance Document on Integrating Palliative Care in Tuberculosis Care at DR-TB Centers [Draft]

Guidance Document on Integrating Palliative Care in Tuberculosis Care at DR-TB Centers [Draft]This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-3.0 IGO license (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this license, you may copy, redistribute, and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. The use of the logos provided in this document is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons license. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the license shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the Government of India.

Suggested citation: Guidance Document on Integrating Palliative Care in Tuberculosis Care at DR-TB Centers, GHTM Tambaram, 2024.

Cataloging-in-Publication (CIP) data:

Contributor author: GHTM Tambaram; Coverage spatial: Chennai, India; Date issued: June 2024; Language: English; Rights: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO;

To submit requests and queries on rights and licensing, write to: ghtmtambaramkancheepuram@gmail.com.

General Disclaimer: All reasonable precautions have been taken by the GHTM Tambaram to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The purpose of this document is to provide guidance on how to integrate palliative care in TB care at DR-TB centers and is not legally binding. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader.

Live Document: Due to the evolving nature of the program the guidelines need to be updated frequently in accordance with it. This would mean that the content would be updated as and when any policy, procedure or technical instructions are changed.

Acknowledgement

AcknowledgementThe guidance document for integration of Palliative Care in Tuberculosis is an initiative by Central TB Division and Government Hospital for Thoracic Medicine, Tambaram Chennai. Special thanks to Dr Sanjay Kumar Mattoo (Addl. DDG- TB, CTD) for spearheading the initiative. The guidelines have been developed as the end product of a series of consultations and meetings of the working committee held under the leadership of Dr P.M Ramesh, Medical Superintendent GHTM, Tambaram, Chennai. An expert group was constituted and was chaired by Dr R. Sridhar (Chettinad Hospital and Research Institute, Chennai).

We express our gratitude to the eminent technical experts for developing this document (alphabetical Order): Dr Alpa Dalal (GTB Hospital, Mumbai), Dr Asha Fredrick (STO TN), Dr B. L Shahshibhushan (BMCRI, Bangalore), Dr Jenifer Jeba (CMC Vellore), Dr Mahilmaran M (Former Director, Institute of Thoracic Medicine Chennai), Dr Padmapriyadarsini, (Former Director, NIRT), Dr Pramila Singh (MSF), Dr Rajani Bhat, (Sparsh Hospital, Bangalore), Dr Rajam Iyer (Bhatia and P.D Hinduja, Hospital, Mumbai), Dr Rakesh P.S (The Union), Dr Rekha Bansal, (LBSGMC, Mandi), Dr Republica Sridhar (TN Palliative Care Society), Dr Sanjeev Nair (Government Medical College, Thrissur), Dr Sreedevi Warrier (Pallium India), Dr Subhakarkandi (Osmania Medical College, Hyderabad), Dr Suma Sivakumar (WHO NTEP TSN), Dr Vinod (Director, Institute of Thoracic Medicine, Chennai), Dr Vijay Chavan (MSF)

We also acknowledge the guidance and support of Dr Malik Parmar (National Professional Officer, WHO India), Dr Jyoti Jaju, Program Director (The Union). Dr Amar Shah (Chief of Infectious Diseases, USAID), DrBhavinVadera (Senior Health Advisor, USAID), Dr Sandeep Chauhan (National Consultant, DR-TB) and Dr Mayank Mittal, (National Consultant, DR-TB). Overall coordination for developing this document was done by Dr Anand (GHTM), Dr Radhika (GHTM), Dr Devanathan (GHTM), Dr BanuRekha VV (NIRT), Dr Dina Nair (NIRT), Dr Meera Bhatia (The Union) and Richard Samuel (The Union).

Acronyms

Acronyms

ACE Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme

ADR Adverse Drug Reaction

ATS American Thoracic Society

ATT Anti-Tuberculosis Therapy

CAD Coronary Artery Disease

CKD Chronic Kidney Disease

CLD Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

CSR Corporate Social Responsibility

DM Diabetes Mellitus

DNA Deoxy Ribonucleic Acid

DTO District Tuberculosis Officer

DRTB Drug Resistant Tuberculosis

DSTB Drug-Sensitive Tuberculosis

ERS European Respiratory Society

HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus

ICP Individualized Care Plan

ICU Intensive Care Unit

INH Isoniazid

IP In Patient

IV Intravenous

SC Subcutaneous

MDR TB Multi Drug Resistant Tuberculosis

RRTB Rifampicin Resistant Tuberculosis

MO-DTC Medical Officer District Tuberculosis Centre

Mos Medical Officer

NGO Non-Governmental Organization

NSAIDS Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

NTEP National Tuberculosis Elimination Program

PMDT Programmatic Management of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis

PMTMBA Pradhan Mantri TB Mukt Bharat Abhiyaan

PTB Pulmonary Tuberculosis

PTLD Post-Tuberculosis Lung Diseases

RNA Ribonucleic Acid

SAM Severe Acute Malnutrition

TB Tuberculosis

TBHV Tuberculosis Health Visitor

TDS- Ter Die Sumendum (3 Times a Day)

BD Twice Daily (Bi-Side)

OD Once a Day

WHO World Health Organization

XDR TB Extensive Drug Resistant Tuberculosis

Introduction & TB Overview

Introduction & TB OverviewIntroduction:

The word “palliate” is derived from the Latin word “pallium”1 meaning cloak i.e. an encompassing care that “cloaks” or protects the people from the misery of symptoms of the disease, whether cure is possible or not. It is person focused and seeks to address the issues which are of utmost concern to the person with illness at that stage.

The World Health Organization (WHO)2 defines palliative care as "an approach that improves the quality of life of patients (adults and children) with life threatening illness and their families through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification, impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other physical, psychosocial or spiritual problems ".

The definition of the palliative care by the Expert group is as follows “A comprehensive multi-disciplinary medical, psychosocial and spiritual approach to identify, evaluate and implement measures to alleviate/minimize the sufferings of people with Pulmonary and Severe forms of extra pulmonary TB, to improve their quality of life, from diagnosis to End of life care”.

There is a misconception that palliative care is only beneficial in the terminal stage of an illness when the role of life-prolonging or curative treatment has terminated. However, the true meaning of palliative care is that it should aim at relieving suffering in all stages of the disease and is not limited to end-of-life care only. Palliative care may be provided along with curative or life-sustaining remedies.

TB Overview:

Tuberculosis (TB) is a contagious bacterial infection primarily affecting the lungs, though it can spread to other organs. It is characterized by symptoms such as persistent cough, dyspnea, chest pain, weight loss and hemoptysis. The disease is both preventable and curable, with early diagnosis and treatment being crucial for control and prevention. The discovery of TB chemotherapy, along with intensified efforts at prevention and cure, resulted in dramatic reductions in TB mortality; but on the other hand, disease has become more complicated and difficult to handle situations have arisen in the form of recurrent TB, Post TB Lung Disease (PTLD) and Drug Resistant tuberculosis.

TB is among the top ten contributors to the global burden of serious health-related suffering. According to the WHO Global TB report 2023, TB was the world’s second leading cause of death from a single infectious agent in 2022 after COVID-19. India accounts for nearly a quarter of the disease burden. In India, in the year 2022, 2,820,000 people were estimated to have developed TB, of which 48,000 were HIV-positive and 1,10,000 were MDR/RR-TB.2 Treatment success rate for TB in India was 87% for new and relapse cases registered in 2021, 78% for HIV positive TB cases registered in 2021, 69% for MDR/RR-TB initiated on second line treatment in 2020 and 64% for Pre-XDR/XDR TB cases initiated on treatment in 2020. Estimated deaths due to TB in the country for 2022 were 342,000.

Need of Palliative care among people with Tuberculosis

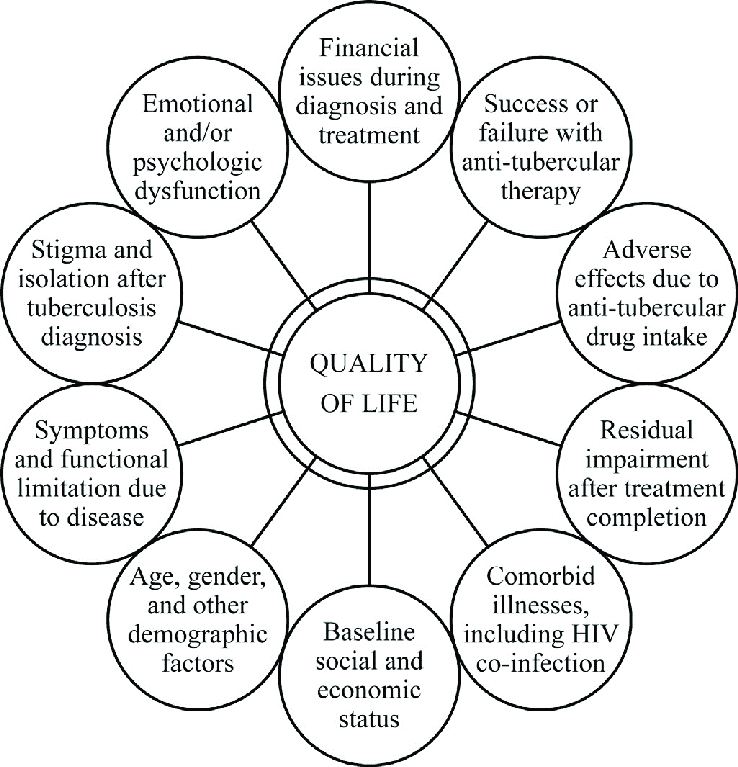

Need of Palliative care among people with TuberculosisThe suffering faced by people with TB and their families may be due to the disease itself, the treatment, co-morbidities and adverse outcomes of anti-tuberculosis drugs. Suffering in TB is multidimensional affecting physical, psychological, social and spiritual domains of the person. Thus, palliative care has a major role in TB and must be integrated into the course of TB care. Every person with TB should be motivated to continue and complete anti-tubercular treatment. For people affected by TB with complex physical, psychosocial or spiritual needs, palliative care should be considered early in the course of illness, in conjunction with disease-directed treatment.

1.Aim of providing palliative care to people with TB

The problems faced by people with TB3 and families span multiple physical, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions. Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of people with TB and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment and treatment of physical, psychosocial or spiritual problems. The aim of palliative care in TB4 should be alleviation of sufferings caused by the primary disease as well as adverse effects of the anti-tubercular drugs to improve the quality of the life during and after completing TB treatment with provision of end-of-life care when required. Integration of palliative care improves treatment outcomes by enhancing treatment adherence and also prevents premature deaths.

2.Key population for providing palliative care

Specific groups who will definitely have increased palliative care needs include those with drug resistance5 (MDR/RR-TB, Pre-XDR/XDR-TB), who are co-infected with HIV, those having severe disease including multi-organ involvement or failure, those with severe forms of extra pulmonary TB and those with recurrent/chronic TB.

Apart from this, there is another group of people who get microbiologically cured but are left with Post TB sequalae also called Post TB Lung Disease (PTLD) including destroyed lung, Fibro cavitory disease, Aspergilloma, Bronchiectasis etc. Up to 50% of people with microbiologically cured TB may be left with permanent, moderate or severe pulmonary function impairment; experience exercise limitations and have a hampered quality of life. This group of people finally land up in Respiratory failure and may require long term care.

3.Challenges in providing palliative care to people with TB

PMDT guidelines 2021 outline the need for palliative care in TB and mandate the Nodal TB Centers to initiate institution-based and community-based palliative care services. Through NTEP, many aspects of palliative care are covered in different forms like home visits by TBHV, counseling by TB counselors, nutritional support through Nikshay Poshan Yojana, peer support through TB champions, community support in the form of Nikshay Mitra, travel allowances, Pradhan Mantri TB Mukt Bharat Abhiyan (PMTMBA) etc. However, palliative care for people with TB and their families remains underdeveloped.

There are two main barriers to advancing the availability of palliative care for TB. Due to the curable nature, there is some inherent resistance to the idea of palliative care for people with TB. The second main barrier is simply the lack of knowledge of palliative care principles and practice among the providers who care for TB.

4. Special considerations for providing palliative care to people with TB

●Large number of people requiring palliative care in TB is infectious, so airborne infection control practices need to be strictly followed.

●People with post TB lung disease (PTLD) may not be contagious (bacteriological evaluation of sputum to be done to rule out active disease) but have significant lung damage in the form of Destroyed lung, Bronchiectasis, Aspergilloma and land up into Type II Respiratory failure over a period of years. Such a group of people can be taken care of by home based palliative care type of model, as they are not contagious

●People with PTLD with compromised lungs may suffer from other health related issues: symptomatic cholelithiasis, symptomatic nephrolithiasis, hernias and require corrective surgeries; but are not taken up for surgeries as may not be fit for anesthesia due to compromised respiratory system. Minimal access surgery options should be incorporated in palliative care services.

●People with recurrent Drug sensitive or Drug Resistant TB with localized disease are eligible candidates for surgical resection of the affected part but are not considered for due to their microbiologically positive status. Moreover, people with DSTB or DRTB who suffer from other surgical problems and need immediate surgeries to relieve the suffering are not entertained just because of their bacteriologically positive status. A guidance document on indications for TB thoracic surgeries and capacity building of surgeons in this regard is required.

● Though dyspnea is the dreaded symptom in extensive PTB and in the majority of people with TB at the end of life; still, TB facilities have limited access to opioids. In low doses, morphine suppresses the respiratory center slightly and has an anti-anxiety effect. This relieves tachypnea, increases tidal volume and oxygenation. Thus, low dose morphine increases effectiveness of respiration in people with hypoxia. Additionally, it also relieves pain. TB institutions with high patient load and providing palliative care need to have access to opioids.

5. Palliative care models for various key population affected by TB

|

Key Population |

Recommended palliative care model |

|---|---|

|

Newly diagnosed microbiologically confirmed/clinically diagnosed TB

|

Integrate palliative care into the package of essential services for TB, prioritizing those individuals who need it. |

|

People with Post TB sequelae |

Traditional Home care-based model along with hospital-based care as and when required |

|

People with recurrent Drug Sensitive TB and Drug Resistant TB |

Hospice based model on the lines of traditional sanatorium-based care along with special consideration to take care of caregivers and infection control measures |

“There is no single recommended model for the provision of palliative care; the best model is determined by local needs and resources

Figure 1 – Ensuring the continuum of Palliative care services for TB7 (adapted from WHO guidelines for Palliative care)

Delivery of Palliative Care: Infrastructure, tools and human resource

Delivery of Palliative Care: Infrastructure, tools and human resourceEffective implementation of palliative care for people with TB requires proper infrastructure and human resources in the centers providing palliative care. People with TB may come from districts far away from centers of excellence and hence there is also a need for linkages to peripheral centers and provision for continued care in these peripheral centers.

In the ideal case scenario, the following are required for delivering palliative care services, particularly in Centre of Excellence for DR-TB care

1. The team of Palliative Care

The palliative care team TB is a multidisciplinary team and consists of:

1. Doctors

2. Nurses

3. Medical Social Workers

4. Nutritionists

5. Respiratory Therapists

6. TB Counselors

7. Clinical Psychologists

8. Psychiatrists

The team should receive training in palliative care (at least 30-40 hours). Following the basic training, the team members should also aim to improve their palliative care skills through advanced training courses. A number of online courses in palliative care are available.

However, human resources expected in the above list may not be available in all centers of excellence, and the basic minimum staff expected to be essential for running palliative care services would include

1.Doctors

a. Clinicians treating people with TB

b. Publichealth doctors providing programmatic services

i.NTEP MOs

ii.PMDT MOs

2.Nurses

3.Counselors

4.Dieticians

5.Physiotherapists / respiratory therapists

6.TB health visitors / treatment organizers

Since this team would be trained in palliative care, however doing palliative care in addition to other duties, there may be need for supportive services from the state / district palliative care team or a linkage with an NGO / private provider who have greater expertise in palliative care.

At the linked nodal DR TB centers, the component of staff expected to provide continued services for patient would be

1.Doctors,

a. Clinicians treating TB patients

b. PMDT MOs

2.Nurses

3.Counselors

4.Dieticians

5.Physiotherapists / respiratory therapists

6.TB health visitors / treatment organizers / Statistical Assistant

At the district DR TB center level DTO, MO DTC, Nurses, TB HVs and counselors will provide continued care to patients referred from the Nodal DR TB centers.

2. Functions of the Palliative Care Team

1.Assessment of palliative care needs of people with TB: The team should assess the people affected by TB in the physical, psychological, social and spiritual domains.

2. Preparation of care plan: Individualized Care Plans (ICP) should be prepared to address the multifaceted needs of people affected by TB and their families.

3. Provision of palliative care

a. Correct the correctable - Correctable causes of suffering should be identified and addressed through a multi-disciplinary approach.

b. Specialist palliative care consultation – For complex palliative care needs a specialist palliative consultation may be done.

4. Documentation and research – The assessment and management done should be properly documented. Contextually relevant research activities should be undertaken.

5. Establishing community linkages - It is important to ensure continuum of care after the patient is discharged and sent home. Hence efforts should be taken to establish linkages with palliative care services available in the patient's locality.

6. Procurement of drugs and equipment required for palliative care e- The team should procure the necessary drugs and equipment required for palliative care and also ensure that the necessary infrastructure is in place.

3. Palliative care Assessment and individualized care plan

Palliative care needs assessment and care plan should be incorporated into the medical records. An additional document will be attached to the treatment card of the patient, which would contain information on assessment done, the individual patient palliative care plan and assessment and monitoring tools to assess progress and response to treatment. The structure of the document is attached in Annexure 1.

4. Infrastructure

Infrastructure requirements follow the principles as that for infection prevention, patient privacy, and quality of life of the patients and caregivers.

●IP care facilities – IP care facilities would be provided as per the NTEP guidelines for Drug sensitive and Drug resistant TB, in concordance with National airborne infection control guidelines

●Adequate open space for recreation, meditation, prayer and counseling.

●A separate place would be designated, with concordance for airborne infection control, for counseling people with TB with privacy.

●Provision for supply of food as per the nutritional needs of the patients, as determined by the dietician and treating doctor.

●Infrastructure should be disabled-friendly with ramps, elevators, toilets etc

●A separate room/private space for imminently dying individuals. If a separate room is not available, privacy should be ensured with screens or curtains.

5. Medications needed

Essential medicines for palliative care according to WHO Essential package of palliative care drugs for people affected by TB and ancillary drugs to manage ADR should be made available. Medications required include drugs for pain control (Paracetamol, Ibuprofen, Diclofenac, Codeine phosphate, Tramadol, Morphine and Gabapentin), drugs for gastrointestinal symptom control (Metoclopramide, Domperidone, Dexamethasone, Bisacodyl, Loperamide, Oral rehydration salts and Ranitidine), materials for wound management (Betadine lotion and ointment, Metronidazole jelly and Hydrogen peroxide), drugs for psychological symptom management (Diazepam, Haloperidol and Amitriptyline), antibiotics and antifungals, nutritional supplements (including high protein and calories food supplements and Iron, vitamin and mineral supplements) and other miscellaneous items (Spirit, Lignocaine jelly, Ethamsylate, Cough suppressants).

6.List of drugs required for palliative care as per WHO Essential drug list

Non-opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines (NSAIMs)

a. Ibuprofen: Oral liquid: 200 mg/5 mL

Tablet: 200 mg; 400 mg; 600 mg.

b. Paracetamol: Oral liquid: 125 mg/5 mL

Suppository: 100 mg.

Tablet: 250 mg / 500 mg /600 mg.

c. Opioid analgesics

Morphine Granules (slow-release; to mix with water):20-200mg (morphine sulfate)

Injection: 10 mg (morphine hydrochloride or morphine sulfate) in 1mL ampoule

Oral liquid: 10mg (morphine hydrochloride or sulfate)/ 5 mL

Tablet (slow release): 10–200mg (morphine hydrochloride or sulfate)

Tablet (immediate release): 10 mg (morphine sulfate)

Medicines for other common symptoms in palliative care

a.Amitriptyline Tablet: 10 mg; 25 mg; 75 mg

b.Cyclizine Injection: 50 mg/ mL

Tablet: 50 mg

c.Dexamethasone Injection: 4 mg/ mL in 1mL ampoule (as disodium phosphate salt)

Oral liquid: 2 mg/5 mL

Tablet: 2 mg; 4 mg

d.Diazepam Injection: 5 mg/mL

Oral liquid: 2 mg/5 mL

Rectal solution: 2.5 mg; 5 mg; 10 mg

Tablet: 5 mg; 10 mg

e.Docusate sodium Capsule: 100 mg

Oral liquid: 50 mg/5 mL

f.Fluoxetine Solid oral dosage form: 20 mg (as hydrochloride).

g.Hyoscine hydrobromide Injection: 400 micrograms/ml600 micrograms/mL

Transdermal patches: 1 mg/72 hours.

h.Lactulose Oral liquid: 3.1–3.7 g/5 ml.

i.Midazolam Injection: 1 mg/ mL; 5 mg/ mL

Solid oral dosage form: 7.5 mg; 15 mg.

Oral liquid: 2mg/ mL

j.Ondansetron Injection: 2 mg base/mL in 2mL ampoule (as hydrochloride)

Oral liquid: 4 mg base/5 mL

Solid oral dosage form: Eq 4 mg base; Eq 8 mg base.

k.Senna Oral liquid: 7.5 mg/5 mL

7. Equipment

The essential equipment required for palliative care in TB are outlined in the WHO operational handbook.2 A summary of the list of equipment from the document is below

List of basic equipment required at Centre for excellence and nodal DR TB centers for palliative care

|

Equipment |

Supplies |

|---|---|

|

Stethoscope |

Dressing supplies |

|

Blood pressure apparatus |

Cotton |

|

Torch |

Scissors |

|

Thermometer |

Gauze pieces |

|

Tongue depressors |

Gauze bandages |

|

Forceps |

Dressing trays |

|

|

Gloves |

|

Supportive equipment |

Micropore tapes |

|

Backrests |

Transfusion supplies |

|

Air mattresses |

IV sets |

|

Water mattresses |

Intracath and butterfly needles |

|

Suction machines |

Syringes and needles |

|

Nebulizers |

Tubes and bags |

|

Wheel chairs |

Suction catheters |

|

Walking frames |

Urinary catheters |

|

Bath chairs |

Condom catheters |

|

Bedpans / commodes |

Urine bags |

|

|

Feeding tubes |

Copies of assessment tools for palliative care, including tools for assessing severity of cough, dyspnea, pain, malnutrition, etc. should be available, and relevant assessment forms may be attached to the patient treatment card / NTEP treatment record.

Psychosocial aspects in the care of people with TB

Psychosocial aspects in the care of people with TBTuberculosis, while treatable, can be a physically and emotionally demanding illness. Palliative care plays a crucial role in addressing the psychological needs of people with TB throughout their journey, not just at the very end. Overall, a holistic approach to palliative care for people with TB recognizes the interconnectedness of physical, emotional, and social well-being. By addressing these psychosocial aspects, alongside physical symptom management, palliative care aims to create a dignified and meaningful experience during and at the final stages of their illness. Palliative care can significantly improve the quality of life for people affected by TB and their families, empowering them to cope with challenges and find meaning throughout their journey.

1. Impact of Psychosocial Factors on TB Outcomes

Studies have established a strong link between unaddressed psychosocial issues and :

● Treatment adherence: Negative emotions and lack of social support can hinder adherence to the lengthy and complex TB treatment regimen.

● Quality of life: TB can significantly impact people’s physical and emotional well-being, leading to social isolation and decreased quality of life.

● Mental health: The disease and its treatment can increase vulnerability to anxiety, depression, and other mental health challenges.

2. Key Psychosocial Concerns

● Anxiety and Fear: The diagnosis of TB can trigger significant anxiety about the course of the disease, potential complications, and associated long-term health implications. Fear of transmission to loved ones and concerns about the stigma associated with TB can further exacerbate anxiety.

● Depression: The physical symptoms of TB, combined with the social isolation and limitations imposed by treatment, can contribute to feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, and loss of control, leading to depression.

● Coping difficulties: Adjusting to the demands of the treatment regimen, including potential side effects and medication adherence, can be challenging. People with TB may struggle to cope with the emotional and practical burdens of the illness, impacting their overall well-being.

● Social isolation: Fear of transmission and the stigma associated with TB can lead to social isolation and withdrawal from social activities. Lack of social support can further exacerbate feelings of loneliness and depression, hindering their coping abilities.

● Stigma and discrimination: While treatable, TB carries a heavy stigma leading to isolation, shame, and anxiety. This stigma negatively impacts mental health, causing depression and anxiety, and hinders treatment adherence through fear of disclosure, causing individuals to avoid seeking or discontinuing treatment, ultimately posing challenges for public health efforts. Addressing this issue through educational campaigns and promoting empathy can create a supportive environment for individuals with TB, leading to better treatment outcomes and a healthier society.

● Coping with the chronic illness: TB treatment can be a significant source of frustration and emotional distress. The lengthy and demanding treatment regimen can lead to feelings of powerlessness and a loss of control over one's life. Individuals may experience frustration due to limitations in daily activities, fatigue caused by medication, and the long duration of the treatment course. This frustration can then morph into feelings of hopelessness and powerlessness, impacting mental well-being and potentially hindering adherence to the treatment plan.

● Psychological distress: The diagnosis of TB, especially in the context of potential complications or even death, can generate overwhelming and debilitating psychological distress for individuals. This intense burden of negative emotions can significantly diminish an individual's quality of life and create roadblocks in their journey of treatment and recovery.

● Lack of access to mental health services: Limited access to mental health care and stigma associated with mental illness can further exacerbate these challenges and hinder recovery.

● Social and economic impact: TB's reach extends beyond individual health, deeply impacting social and economic well-being. The lengthy treatment schedule can disrupt work, leading to loss of income and potential loss of job . This financial strain creates additional stress, while the fear of stigma and discrimination can lead to social isolation and disruption of relationships. The combined effect of these factors can trap individuals and their families in a cycle of poverty, further hindering access to proper healthcare and perpetuating the burden of TB on individuals and society at large.

● Spiritual challenges: Facing a life-threatening illness raises profound questions about life, death, and purpose, creating a need for spiritual support and meaning-making.

3. People at different stages of illness require different types of psychological support

i) People in the diagnostic phase

Acute stress response has been described as the usual response to the diagnosis of TB. The response is characterized by shock, disbelief, anxiety, depression, sleep and appetite disturbance and difficulty performing activities of daily living. Patients and families often experience fear, concerns and isolation during this period. Early assessment by clinicians can help identify individuals who are at greatest need of ongoing psychosocial support.

Often times recurrence and repeated episode of the disease could be very distressing to the patient, with an increase in depression anxiety suicidal ideation, such a situation requires psychological support and a holistic medical care which is possible through palliative care.

Factors that may predict poor coping mechanism are as follow:

● Past psychiatric history

● Limited social support

● Alcohol or drug abuse

● Recent losses

● Advanced disease

ii) During the course of disease: As uncomfortable symptoms increase, perceived quality of life diminishes. Thus, an important goal in the psychosocial treatment of the people with advanced TB is control of the physical symptoms.

There is a need for health care professionals to establish structured dialogue with patients and family members. Psychiatric consultation liaisons nurses, psychiatrists, social workers and program staff are invaluable resources in the decision-making process about treatment options in advanced stages.

Positive coping strategies, such as taking action and finding a favorable coping mechanism in the situation, have been reported as effective.

iii) People in the terminal stage of illness

Palliative care can relieve physical and psychological symptoms and promote comfort and wellbeing to the point of death. Patients and families who have received such services along with illness trajectory often will be more open to palliative efforts in the final stage of life.

4. Addressing emotional needs

Palliative care teams play a vital role in addressing the psychological needs. This includes providing:

● Assessment: Comprehensive assessment of patients' emotional, social, and spiritual needs using standardized tools and open-ended discussions.

● Active listening and validation: In tackling the psychological challenges linked to TB, active listening and validation are crucial. This involves healthcare providers creating a safe and supportive environment where patients feel comfortable expressing their worries, anxieties, and frustrations openly and without judgment. By actively listening and validating their emotions, healthcare providers can build trust, foster empathy, and empower patients to participate actively in their treatment journey, ultimately leading to better treatment outcomes and improved mental and social well-being.

● Psychotherapy and counseling: Psychotherapy and counseling can play a vital role in supporting individuals with TB manage the emotional challenges associated with the disease. These interventions, offered through individual or family therapy sessions, help address specific issues like anxiety or depression. Therapists use various techniques to equip people with coping mechanisms, improve their emotional well-being, and foster resilience in dealing with the demands of their diagnosis and treatment. By addressing these psychological burdens, therapy can empower individuals to adhere to treatment plans, improve their overall quality of life, and contribute to better treatment outcomes.

● Spiritual support: Spiritual support can be a valuable resource for individuals with TB, if they desire it. This type of support, provided by chaplains, religious leaders, or spiritual guides, can offer patients a sense of meaning and purpose in their illness journey. They can help individuals find peace and comfort through prayer, meditation, or religious practices, fostering a sense of hope and resilience. However, it's crucial to remember that spiritual support is not a substitute for medical treatment and should always be offered with respect for individual beliefs and preferences.

5. Building a Support system

Palliative care also emphasizes the importance of building a strong support system. This includes:

Family counseling: The emotional strain of TB isn't confined to the individual. Family counseling can play a crucial role in supporting families impacted by TB. Therapists can facilitate open communication between family members, helping them express their concerns and anxieties in a safe space. Additionally, family counseling can equip families with coping mechanisms to handle the emotional and logistical challenges associated with caring for a loved one with TB, ultimately fostering a supportive and unified environment conducive to healing.

Social support groups: The feeling of isolation can be a major challenge for individuals battling TB. Social support groups provide a platform for connecting with others facing similar experiences, fostering a sense of belonging and reducing isolation. By sharing experiences, challenges, and successes within these groups, individuals can find emotional support, encouragement, and valuable insights from others who understand their unique journey. This sense of community can empower individuals to feel less alone and more resilient in their fight against TB.

TB Champions: A TB Champion3 is a person who has been affected by TB and successfully completed the treatment. They act as role models and can provide valuable support to those with TB and their families. The services these champions can be utilized in TB palliative care

6. Strategies for Effective Psychosocial Care Delivery

Multidisciplinary team approach: Collaboration between healthcare professionals, social workers, counselors, and spiritual care providers is crucial for holistic care.

Culturally sensitive care: Recognizing and respecting the diverse cultural and religious backgrounds of patients.

Empowerment and education: Empowering affected people with information about their illness, treatment options, and available psychosocial support services.

Community involvement: Engaging community resources and support groups to create a network of support beyond the healthcare setting

7. Key Socioeconomic Challenges

● Loss of Income: TB can lead to lost income due to missed workdays, diminished ability to work, or loss of job due to stigma. This can create financial strain and threaten basic needs like housing and food security.

● Food Insecurity: TB treatment can worsen existing food insecurity due to the illness itself, financial limitations, and dietary restrictions. Inadequate nutrition can compromise treatment outcomes and overall well-being.

● Access to Healthcare: Poverty and lack of health insurance can create barriers to accessing necessary healthcare services, including medications, consultations, and diagnostics, further hindering effective treatment and management.

● Education and Employment: TB can disrupt education and career opportunities due to illness, treatment schedules, and potential stigma. This can limit future earning potential and perpetuate the cycle of poverty.

8.Palliative Care's Role in Addressing Socioeconomic Needs

● Needs Assessment: A comprehensive assessment of the affected individual’s social and economic circumstances is crucial to identify specific needs and tailor interventions accordingly.

● Social Support: Connecting affected people with social workers, community resources, and relevant government programs to provide financial assistance, food aid, and access to basic necessities.

● Vocational Rehabilitation: Supporting skills development and retraining programs can empower affected individuals to re-enter the workforce and improve their long-term financial stability.

9. Empowering People with TB

● Information and Education: Ensure people affected with TB have access to accurate and culturally sensitive information about TB, treatment options, and available support services. This empowers them to make informed decisions about their healthcare and navigate the challenges of the disease.

● Shared Decision-making: Encourage healthcare providers to adopt a collaborative approach to treatment planning, involving patients in decision-making processes. This fosters a sense of empowerment and control over their treatment journey.

● Life Skills Training: Offer skills training programs to help people affected by TB to develop practical skills for managing finances, navigating the healthcare system, and advocating for their needs. This empowers them to face the challenges of the disease and build a sense of self-confidence. Life skills training programs for people with TB aim to equip them with practical skills and knowledge to navigate the challenges associated with the disease and improve their overall well-being. These programs typically focus on the following key areas:

(i) Self-Management:

● Medication Adherence: Educating people with TB on the importance of medication adherence, potential side effects, and strategies for managing them effectively. This can involve developing medication schedules, using reminders, and addressing medication-related concerns.

● Symptom Management: Training patients on identifying and managing common symptoms of TB, such as fatigue, cough, and loss of appetite. This includes self-care techniques, breathing exercises, and understanding when to seek medical attention.

● Nutritional Management: Providing guidance on healthy eating habits to maintain a balanced diet and support the immune system during treatment.

(ii) Communication and Advocacy:

1. Effective communication with healthcare providers: Training affected people on how to effectively communicate their symptoms, concerns, and needs to healthcare professionals. This enables them to actively participate in their treatment decisions and ensure they receive adequate support.

2. Advocacy for themselves and others: Empowering patients to advocate for their rights and access to healthcare services. This can involve learning about relevant support programs, addressing stigma and discrimination, and advocating for policy changes that improve TB care delivery.

(iii) Financial Management:

● Budgeting and financial planning: Helping people manage their finances effectively. This can include coping with potential income loss due to illness and exploring available financial assistance programs.

● Accessing healthcare resources: Guiding people with TB on navigating the healthcare system, understanding insurance coverage, and accessing necessary resources for treatment and follow-up care.

Physical Symptom Management

Physical Symptom ManagementThe main aim of palliative care is to improve quality of life for the patient with the help of symptomatic treatment and relief of suffering.

The following symptoms occur often in progressive tuberculosis: cough and shortness of breath, hemoptysis and bleeding, anorexia and cachexia, pain, night sweats, anxiety and depression.

People with Drug Resistant TB may have more intensity of disease and adverse effects to the medications.

1. Cough

Among people with pulmonary tuberculosis, including M/XDR-TB, cough is persistent. Nevertheless, cough may be caused by other reasons such as non-specific pulmonary infections, Influenza, COPD and Bronchiectasis, pulmonary tumor (Kaposi’s sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma in HIV-positive patients with tuberculosis), aspiration, and sinusitis following treatment with nasal drops, gastro-esophageal reflux, and spontaneous pneumothorax.

Management of Cough:

For cough caused by mucus hyper-production, use steam inhalations. If the volume of sputum exceeds 30 ml per day, forced expiration technique with postural drainage should be applied.

For people with mild cough, a trial of nonpharmacologic therapies may be attempted as a first step8. Options include use of linctus such as honey, breathing exercises, cough suppression techniques, and patient counseling. If these are ineffective, we then suggest a peripherally acting antitussive (eg, Benzonatate13 100 mg TDS). Other peripherally acting antitussives include levodropropizine and levocloperastine available as cough syrup9,10

For cough with serous sputum use any of the following:

● Antihistamines, e.g., Levocetrizine, 5mg, once at night time after food

● Hyoscine 10 mg in every 8 hours. Hyoscinebutyl bromide: 20 - 120 mg in oral doses taken at certain intervals, or via continuous subcutaneous infusion

● Scopolamine transdermal patch: 1.5 mg; 1 - 3 patches applied every 72 hours

For cough caused by bronchial spasm, use any of the following:

● Oral bronchodilators, eg.,Acebrophylline 100mg twice a day after food

● Inhaled bronchodilators e.g. nebulization with levo salbutamol 0.63mg every 6th hourly till symptoms resolve.

● Oral corticosteroids eg., Prednisolone 0.5-1 mg per kg given in two divided doses

For cough caused by gastric reflux, use;

● Proton-pump inhibitors eg.,Pantoprazole 40 mg morning and night before food

For dry, non-productive cough, use:

● Dextromethorphan11 - 25 mg TDS; morphine – starting from 2.5 mg every 4 hours or

● Lidocaine inhalation12 3-5 ml 2% solution 3-4 times a day

For productive cough in patients who cannot cough effectively, use:

● Inhalations with 3 % Hypertonic saline solution – 5 ml every 4th hourly

● Mucolytics – Acetylcysteine, Bromhexine.

For productive cough in physically weak patients, use any of the following:

● Codeine 10- 20mg every 4 hours, not more than 60 mg a day

● Morphine 2.5mg-5mg every 4 hours

● Dextromethorphan 25-50 mg 3-4 times a day

For drug induced cough

● Stop drugs like ACE inhibitors and sitagliptin which can cause cough

For moderate to severe cough, use

● Morphine 2.5mg-5mg every 4 hour or

● Gabapentin14 300mg OD or Pregabalin 75mg OD

2. Shortness of Breath

The most effective drugs for treatment of shortness of breath are opioid analgesics such as Morphine (2.5mg-5mg) every 4 hours. Additional Oxygen may be especially useful for patients with hypoxia. The air is supplied by a fan or an open window, which can reduce shortness of breath by stimulating sensory receptors on the face and in the epipharynx.

3. Hemoptysis

Hemoptysis is blood coughed up from a pulmonary source. Hemoptysis must be differentiated from pseudo hemoptysis (expectoration of blood originating in the nasopharynx or oropharynx) and hematemesis (vomiting of blood).

Hemoptysis is usually caused by TB; however, it can be as well related to bronchiectasis, aspergilloma, bronchitis, thromboembolism, or tumor.

The use of red towels, dark sheets and blood collection containers can calm the patients with severe hemoptysis.

People with life-threatening hemoptysis should be immediately placed into a position in which the presumed bleeding lung is in the dependent position.

Antifibrinolytic agents like Tranexamic acid15,16 (500mg BD) acts by blocking the breakdown of blood clots, which in turn prevents bleeding. If hemoptysis is overwhelming and/or accompanied by hemodynamic instability and the goals of care do not support attempts at diagnosis or intervention, urgent sedation (midazolam at 0.2 mg/kg IV/SC) may be required.

4. Fatigue17 and Extreme Emaciation

This is one of the most frequent problems among people with TB. A comprehensive history and physical examination are indicated to identify potentially reversible etiologies such as depression or hypothyroidism. A review of all medications, both prescription and over the counter, is particularly important to identify side effects and potential drug-drug interactions that may be contributing to fatigue. Simply altering the dose or dosing interval may substantially improve fatigue. Other considerations for managing fatigue and extreme emaciations are:

● Psycho-stimulants (Modafinil 200 mg OD) and antidepressants may be useful in managing subjective symptoms of fatigue.

● Patients with severe anemia may be helped with blood transfusion18

● Prednisolone 5-15mg a day, up to 6 weeks, can be useful in the event of severe anorexia and asthenia19;

● Vitamin B1 should be administered daily since it plays a core role in production of energy from carbohydrates and is involved in RNA and DNA production;

● In the event of nausea and vomiting, prescribe antiemetic agents

● Provide information on coping strategies that conserve energy and information on good sleep hygiene

● Complementary medicine and nonpharmacologic approaches are available and may include ginseng, exercise, yoga, and cognitive-behavioral therapy, including mindfulness-based stress reduction

● Offer small but frequent portions of favorite food to the patient; do not force the patient to eat. Food should be taken in small portions until appetite revives.

5. Night Sweats

Night sweats are a common non-specific symptom that accompanies TB and M/XDR-TB. Treatment of fever with paracetamol, drinking plenty of water and frequent change of bed sheets and clothes may be advised.

6. Pain

Pain may have various origins in patients with TB and M/XDR-TB, i.e. they can be associated with the organ affected by tuberculosis, as well as for other reasons. It is essential to identify the source of the pain and to manage it properly

The causes of pain in the event of tuberculosis or M/XDR-TB may be as follows:

● Pulmonary or pleural inflammatory infiltration, or other internal organs;

● Muscle tension due to severe cough;

● Bone pain due to TB infiltration in the vertebral column or bones;

●Pain caused by arthralgia or septic arthritis

Management of Pain

Mild pain: Acetaminophen 500mg every 4-6 hours (not to exceed 4g/day); (59)

Moderate pain: Codeine phosphate 30-60mg every 4 hours;

Severe pain: Morphine sulphate 5-10mg every 4 hours, titrated to comfort;

Bone pain: Ibuprofen 200-400mg every 8 hours with antiulcer coverage;

Neuropathic pain: Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) 100mg and tricyclic antidepressants (Amitriptyline 25mg before bed)

Addressing co-morbidities among people with Tuberculosis and its interdisciplinary approach

Addressing co-morbidities among people with Tuberculosis and its interdisciplinary approachCo-morbidities add to the morbidity and mortality of many people with TB and addressing the co-morbidities must be a part of the holistic palliative care approach of TB patients.

Common co-morbidities encountered in practice, include -

• Diabetes mellitus20, HIV and depression, which are the commonest associations. Other co-morbidities include chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease, malignancies, chronic liver disease and COPD21.

• Malnutrition is another area of focus, being both a cause and consequence of Tuberculosis.

• Occupational lung diseases like Silicosis add to the morbidity of lung damage caused by Tuberculosis.

• Another issue that needs to be addressed is substance abuse including nicotine dependence, alcoholism and the use of recreational drugs.

1. Diabetes mellitus

India, being the Diabetes capital of the world, Diabetes is the commonest co-morbidity encountered among people with Tuberculosis22,23,24. Diabetes is associated with a twofold risk of death during TB treatment, a fourfold risk of TB relapse after treatment completion and a twofold risk of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB)22. The palliative care team needs to be aware of the need to manage the co-morbidities of DM and TB together. Issues that need to be addressed include insulin requirements and dosing of the patient, pill burden of adding more drugs to the wide repertoire of drugs already being used by the patient and addressing various acute and chronic complications of diabetes like diabetic ketoacidosis, hypoglycemia, the various vascular and neurological complications of diabetes. While planning a palliative care unit, the focus of the administrator should be on procuring adequate glucometers and consumables for monitoring blood sugar in the palliative care ward, training health care workers including the staff nurses on basic diabetic management like for example using a sliding scale for managing sugar, focusing on preventing complications of Diabetes like foot care, avoiding bed sores etc.and having a specialist physician or diabetologist on call to attend to the complicated cases. The Central TB division, Government of India has provided resources on the management of TB – DM23.

2. HIV

Another common co-morbidity that needs attention is HIV and its complications. The dreadful duo of HIV- TB co-infection is still a cause of high mortality in our country. Though TB is manifested across the spectrum of HIV illness irrespective of the CD4 count, the clinical presentation varies and an awareness of a thorough clinical evaluation and investigation needs to be highlighted to the palliative care team. Issues that need to be assessed also include compliance to medications both anti- retroviral and anti- tuberculous therapy. The added pill burden, the side effects, issues in swallowing these pills due to presence of other opportunistic infections like esophageal candidiasis have to be evaluated. A periodic monitoring of the liver and renal parameters and issues with tolerance of medications are areas to be addressed. The national guidelines for HIV care issued by the National Aids control organization, Government of India26deals extensively with management of HIV TB and will be a useful resource for the palliative care team.

3. CAD (Coronary Artery Disease)

Other co-morbidities that need addressing include coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease and malignancies21. Given the high prevalence of smoking among people developing Tuberculosis, CAD is a common ailment in this cohort of patients and one of the leading causes of mortality. A specialist opinion, where feasible, could be obtained or the palliative care physician can be trained in basic management like using antiplatelet for the needy patients.

4. CKD (Chronic Kidney Disease)

Chronic kidney patients including those on dialysis need modification of drugs which can be done by a physician or specialist based on the availability. The dosing of drugs can be referred to from various guidelines27. Also, in this cohort of patients, a judicious enquiry in to the shadows in an X-ray which could be due to fluid overload, or secondary bacterial, viral and fungal infections are needed. Special considerations including use of Rifampicin and other ATT drugs in post-transplant patients should be done in consultation with the concerned specialists.

5. CLD (Chronic Liver Disease)

Chronic liver disease issues include selection and dosage of drugs to be used and this needs to be guided by the Child Pugh classification and use of non or less hepatotoxic drugs in these patients, with a periodic assessment of the liver function. It is not uncommon, in our country to see patients continuing consuming alcohol even while on treatment of Tuberculosis leading to poor outcome and adverse events29,30,31 and in the setting of palliative care, the guidance of a psychologist or psychiatrist may be crucial.

6. Malignancy

With increasing longevity, there is a rising incidence of various malignancies and this co-morbidity too needs to be addressed. People with malignancy, are per se prone to Tuberculosis due to their immuno-suppression and also become liable to TB due to immuno-suppression created by chemotherapeutic agents32,33,34. Patients with esophageal malignancy have dysphagia to even liquids and it would be unrealistic to expect the patient to swallow the big ATT pills. A tailored regimen to suit the individual’s needs is needed and specialist consultation obtained. Another area that needs to be addressed in these patients is management of TB infection. Pain amelioration is another area to focus on in this group of patients.

7. COPD

COPD and other lung ailments are also co-morbidities commonly encountered in daily practice. Breathlessness, for all we know, may not always be due to parenchymal involvement in the phthisic patient but due to airway involvement in COPD. COPD or other co-morbidities like bronchiectasis or underlying interstitial lung disease, occupational lung disease should be treated optimally with inhaled bronchodilators and appropriate disease-modifying medications. Patients with moderate to severe obstructive or restrictive lung disease will benefit from pulmonary rehabilitation, and palliation of chronic refractory breathlessness with opioids if symptoms persist despite optimization of medications35,36.

8. Substance abuse

Substance abuse disorders like nicotine dependence, alcoholism, recreational drug use which are associated issues also need to be addressed by linkages to de-addiction, smoking cessation clinics, counseling and behavioral change. The central TB division, Government of India has created a framework for collaborative efforts in this regard37.

9. Malnutrition

Last but not the least, another area to be managed is undernutrition which is associated with higher morbidity and mortality in patients with Tuberculosis, being both a cause and effect of Tuberculosis and is also associated with higher hepatotoxicity of ATT drugs38,39. A comprehensive plan to address the individual nutritional needs of the patient on palliative care taking into consideration his caloric and protein requirements, the feasibility and local availability, and also addressing the individual’s food needs to be worked out.

10. IRIS

TB-IRIS may occur in up to one third of patients who have been diagnosed with TB and started on ART. It typically presents within 3 months of the initiation of ART but can occur as early as 5 days. It usually presents with appearance of new or worsening of existing TB signs and symptoms and may be accompanied with increase in size or number of enlarged lymph nodes, appearance of new sites of TB, radiological deterioration etc. Such cases would require the use of anti-inflammatory drugs, including corticosteroids.

Nutritional support for people with TB

Nutritional support for people with TBNutritional status is a widely prevalent comorbidity and risk factor for tuberculosis (TB) disease and mortality. Impaired nutrition increases the risk of severe disease, death, drug toxicity, and malabsorption and relapse. Undernutrition poses serious implications for TB patients and nutritional support is necessary to address this. Undernourished people with TB in the absence of nutritional care get entangled in a vicious cycle of worsening disease and undernutrition.

People with TB who get nutritional interventions have a reduced death rate, better weight gain and body composition, an early sputum conversion, better absorption of drugs, an improved functional status, and adherence. Nutrition screening, evaluation, and management are thus essential for TB treatment and care.

Individualized nutritional management should be proposed by a multidisciplinary team by thoroughly explaining the benefits and drawbacks of feeding options to the patient, family, and caregiver. Artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH) are an essential component of palliative care and can improve quality of life in certain patients based on the severity of TB disease. Therefore, the goals of nutrition in palliative care and at the end of life aim at improving the quality of life.

The guiding principles for nutritional care and support in TB care are mentioned in detail in the guidance document.

-

Nutritional evaluation :

The patient’s height and weight should be recorded by the treating physician at the beginning of treatment. In case of children, the nutritional status can be ascertained using the Z scores for weight for height. The mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) may be recorded in adults who are unable to stand. The weight for height and Body mass index (BMI) charts can act as the reference for children and adolescents to assess the degree of undernutrition. Vital sign assessments may reveal a patient’s requirement for inpatient care. Patients with exceptionally low BMIs (< 14 kg/m2) will require admission for further management.

1.Every individual with active TB should get diagnosis, treatment, and care.

2.A sufficient diet that includes all necessary macro- and micronutrients is important for all those with TB infection and disease.

3.The causal relationship between undernutrition and active TB warrants nutritional screening, assessment, and management

4.It is crucial to identify and resolve the prevailing socio-economic problems like food insecurity and poverty that are both causes and effects of TB.

5.The associated comorbid conditions like HIV, diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, smoking, and drug addiction should be addressed.

2. Nutritional counseling

This includes evaluating the patient's current food intake, learning about their dietary preferences, and talking about the right diet in terms of its composition, frequency of meals, and snacking schedule. The patient should receive guidance on how to use foods that are readily available in their area to boost their calorie and nutrient density. It should be emphasized and explained to the family members that the nutritional supplement (milk powder, groundnuts, and pulses) provided is a form of medication for the patient to assure recovery of the lost weight and muscle mass.

Nutritional support should be prescribed in accordance with the client’s energy and protein needs, disease stage; tolerability and most importantly the wishes and preferences of the patient, family, and caregivers.

3. Provision of nutritional support40

a) Mobilizing the resources through the Local Self-Government initiatives, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), NGOs, philanthropists or inter sectoral collaboration (egTribal Affairs)

b) Delivery of enhanced ration through linkage with the public distribution system for the duration of anti-TB treatment along with a supplement food basket (Antyodaya Anna Yojana).

c) Linkage to Nikshay Poshan Yojana and PMTMBA

d) Severe acute malnutrition may be treated at the inpatient facility of a TB hospital, community health centre, district hospital, or medical college.

e) Social protection measures are required as part of patient-centred care to guarantee long term food security to the person affected by TB and their households.

4. Management of moderate to severe undernutrition

Nutritional support and care are important to improve the health outcomes for people with TB. Food assistance as a component of a service package is expected to enhance treatment adherence and reduce the financial burden of TB. Provision of wholesome food from the government could help to overcome the stigma associated with the disease.

Food assistance should address the nutrient gap by enhancing the energy and protein intake of the client. In addition, providing a food basket for family members to combat food insecurity, chronic energy deficiency, and risk of developing tuberculosis would also be beneficial.

The food assistance package recommended would consist of enhanced ration for patient with TB and family through PDS for the entire treatment period. It should also provide food supplements with high quality protein sources including pulses, oilseeds, and dried milk powder). The various food assistance packages suggested are elaborated in the guidance document.

5. Severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in active TB

Severe undernutrition is linked to a two-four-fold increased risk of death. A comprehensive clinical evaluation of the patient should be done along with the nutritional assessment to look for red flag indications and necessitate hospitalization for treatment. Individuals at risk of unfavorable consequences and death could be admitted to a suitable medical facility in order to stabilize their condition at the initiation of TB treatment.

The background knowledge of organ and systems dysfunction is crucial for the management of severe malnutrition. The phases of management of people with severe malnutrition include initial treatment (stabilization), rehabilitation and follow up. Hypoglycemia, hypothermia, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance should be corrected and infections should be treated.

Since individuals with SAM have infections, decreased liver and intestinal function, and electrolyte imbalance, the F-75 formula feed is advised for nutritional therapy in SAM, which has 75 calories per 100 milliliters and lower levels of protein, fat, and sodium. Locally obtainable ingredients such as cow's milk or skim milk, sugar, cereal flour, and oil can be used to produce an F-75 meal for adults. The recommended daily volume of F-75 should be between 70 and 80 ml/kg.

Food must be provided often and in little amounts to prevent overloading the kidneys, liver, and intestines. The diet should be provided to patients who are able to eat every two, three, or four hours, day or night. In case of vomiting, reducing the amount given at each feeding as well as the time between feedings is advised. Micronutrient deficiencies are widespread in SAM and should be addressed since they affect immunity.

Nasogastric feeding can be considered in individuals with severe anorexia, stomatitis, glossitis, or frequent vomiting; severe dysphagia or odynophagia from any cause; individuals suffering from tuberculous meningitis with an altered sensorium; and critically ill patients experiencing shock.

The risk of refeeding syndrome as a consequence of nutritional therapy for patients with severe malnutrition needs to be addressed. To avoid this, it is critical to recognize these imbalances at baseline and treat them with a mineral mix.

End of Life Care

End of Life CareEnd of life care refers to health care provided in the time leading up to a person’s death. End of life care can be provided in the hours, days or months before a person dies and encompasses care and support for a person’s mental and emotional needs, physical comfort, spiritual needs and practical tasks.41

End of life care is most commonly provided at home, in hospital, or in a long-term care facility with care being provided by family members, nurses, social workers, physicians and other support staff.41

Decisions on End-of-life care are often informed by medical, financial and other ethical considerations.41

1. Supportive measures:42

1)Relief from dyspnea:

Oxygen may be used to alleviate shortness of breath in some cases but there is no significant evidence to generalize its practice. Morphine provides significant relief from respiratory insufficiency and should be offered according to established clinical protocols available.

2)Relief from pain and other symptoms:

Paracetamol, or codeine with paracetamol gives relief from moderate pain. Stronger analgesics, including morphine, should be used when appropriate to keep the patient adequately comfortable. Inj. Morphine 5-10 mg bolus followed by continuous infusion of 50% bolus dose/hr, repeat bolus dose/titrate infusion dose. The WHO has developed analgesic guides, pain scales and a three- step "ladder" for pain relief.

3)Infection control measures:

Infection control measures should be continued with reinforcement of environmental and personal protective measures, including use of N-95 mask use for caregivers wherever indicated.

4)Nutritional support:

Small and frequent meals are often best for a person at the end of life. Intake will reduce as the patient's condition deteriorates and during end-of-life care. Nausea and vomiting or any other conditions that interfere with nutritional support should be treated.

5)Regular medical visits:

Regular visits by health-care providers and the support team should be continued to address medical needs and ensure that infection control practices are being followed.

6)Continuation of ancillary medicines:

All necessary ancillary medications should be continued as needed. Codeine helps control cough, as well as pain. Other cough suppressants can be added. Bronchospasms can be controlled with a metered- dose inhaler with a spacer or mask. Depression and anxiety, if present, should be addressed. Antiemetics may still be needed and fever treated if the patient is uncomfortable.

7)Hospitalization, hospice care or nursing home care:

Home-based care should be offered to people with TB based on the wishes of the person and the families. Appropriate infection control practices need to be followed. Institution based end- of-life care should be made available to those for whom home care is not feasible or desirable. Air borne infection control is essential at institutions providing end of life care to people with TB.

8)Preventive measures:

Oral care, prevention of bedsores, bathing and prevention of muscle contractures are indicated in all patients. Regular scheduled movement of the bedridden patient is very important. Encourage patients to move their bodies in bed if able. Keeping beds dry and clean are also important.

9)Provide psychosocial support:

Psychological counseling to the client and family caregivers is critical at this stage, especially to assist patients in the planning of decisions related with the end of life, and provide emotional support, especially in settings in which strong stigma is attached to the disease.

10)Respect for client’s beliefs and values at the end of life:

It is common for the person and family caregivers to develop or increase their interest in spiritual and religious matters once they perceive that the end of life is approaching. The health- care providers should respect those beliefs and should not impose personal values and practices that prevent the patient from seeking and finding comfort in the services delivered by faith-based organizations.

2. Consensus Position Statements:43

1. Quality of dying is as important as other measures of quality of ICU care

2. While discussing transitioning to complete palliative care, priority should be on minimizing the patient's suffering.

3. Along with terminal illness and impending mortality, severe irreversible disability burdensome to the person should be included as a reason for a treatment limitation decision.

4. ICU admission criteria should exclude patients whose disease/clinical status would clearly render ICU care to be of little or no benefit.

5. Once an End of life care plan is made for client, ICU admission or continuation in ICU is justified in the following circumstances to facilitate -Symptoms control when it is difficult outside the ICU, having ensured that the goals of care are well communicated to the family and are given aid

3. Constituents of a Good Death:43

1. Effective communication and relationship with health-care providers

2. Performance of cultural, religious, or other spiritual rituals

3. Relief from emotional distress or other forms of psychological stress

4. Autonomy with regards to treatment-related decision making

5. Dying at the preferred place

6 Not prolonging life unnecessarily

7. Awareness of the deep significance of what is happening

8. Emotional support from family and friends

9. Not being a burden on anyone

10. Relief from physical pain and other physical symptoms.

4. Ten steps of End of life care pathway:43

STEP 1) Physician reflective prognostic assessment of potentially inappropriate life sustaining treatments. Combining objective and subjective assessments is more reliable than scoring systems alone.

STEP 2) Consistency among healthcare professionals: Physicians and other specialists involved in the care should forge a consensus for the goals of care to be proposed to the client/family.

STEP 3) Early and as needed multidisciplinary patient/family meetings. In the infrequent instance of a capable patient in the ICU willing to participate in decision making, direct communication with due sensitivity should be attempted. The first multidisciplinary family meeting should be within 48 hours commonly occurring before clinical deterioration.

STEP 4) Shared decision making for treatment limitation decision: for capable and informed patients conveying preferences directly, it is settled ethically and legally that decisions are to be implemented without any further process. For a patient without capacity, if a valid advanced medical directive is in place with life sustaining treatment refusal, it must be respected and implemented and conveyed and conveyed to the appointed proxy and family.

STEP 5) Ensure consistency of care plan: Care of an ICU patient passes through multiple hands in a 24-hour period. Debriefing of members not participating in the multidisciplinary family meeting is essential.

STEP 6) Approval from secondary medical board: In compliance with Supreme Court ruling, any foregoing of life sustaining treatment decisions by the primary medical board should be referred to a secondary medical board. The Supreme Court directs an expeditious response within 48 hours.

STEP 7) Implement withdrawal of life sustaining treatments or withholding of life sustaining treatments decision: while implementing it, a palliative care should be in place. Palliative care is best provided in consultation with a palliative care specialist or in a palliative care unit.30

STEP 8) Address physical, emotional and spiritual needs of the patient and family. Monitoring for physical symptoms and titration of doses is imperative. Emotional and spiritual /existential pain must be mitigated. Discontinue routine activities burdensome for the dying patient

STEP 9) Grief and bereavement support: The presence of physicians at the time of death is supportive education of caregiving teams for bereavement support is helpful offering distressed family members the opportunity to address queries or simply for support

STEP 10) Oversight and quality control of care process: A clinical ethics committee including Director or Chief Administrator or equivalent or nominee.

5. Reasons for communication intervention in End of Life Care:43

1. To elicit complete information from the family/surrogates, i.e., history of the illness since patients are often too ill to be able to speak for themselves.

2. To build trust and confidence with patients and families essential to providing emotional support.

3. For conveying prognostic information ensuring family's comprehension and goal-concordant care

4. To break bad news tactfully.

5. To elicit the patient's values and wishes from family/surrogates to initiate conversations around Goals of care in patients facing terminal illness.

6. To accomplish shared-decision-making for Foregoing life sustaining treatment decisions.

7. So far it is possible to prevent or resolve conflicts with families.

8. To resolve conflicts within the treating team.

9. To provide colleagues a supportive climate to foster professional integrity and satisfaction preventing burnout.

6.Conduct of a multidisciplinary family meeting:

At the first meeting

● Have a suitable meeting place

● Ensure all relevant people attend the meeting

● Have enough time with minimal interruptions

● Use vernacular where necessary

● Build a relationship

● Value and respect patient/family Take care of nonverbal communication

● Gather information. Connect to the story. Talk less, hear them out.

● Allow expression of concern

● Identify and support emotion, talking freely helps families

● Provide information tactfully in non-technical language. Provide treatment options. Open conversations about the patient as a person and values.

● Be empathetic. Be kind

● Convey and discuss uncertainties. Recognize end of life needs early

● Avoid focusing on numbers and statistics and outline a plan making sure it is understood.

At subsequent meetings

● Ask-tell-ask at the beginning (ask what they know, then clarify, ensure they have understood)

● Update status;more frequently if things are not going well

● Allow expression of concern

● Identify and support emotions

● Ask-tell-ask

● Summarize and way forward.

7. Breaking bad news (Disclosure of unfavorable information):

Use the SPIKES protocol

● Setting up

● Perception

● Invitation

● Knowledge and Information

● Emotions and

● Empathy

8. Legal Position on EOLC in India:43

There are five key legal principles concerning End of life care in India-

1. An adult patient capable of making health care decisions may refuse life support even if it results in death

2. Life sustaining treatments may be withheld or withdrawn under certain conditions from persons who no longer retain decision making capacity.

3. Advanced Medical Directive that meets specified requirements are legally valid documents.

4. Active Euthanasia “is not lawful

5. The provision of pain relief measures that may incidentally shorten life are lawful and do not constitute: active euthanasia"

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

Pulmonary RehabilitationAmerican Thoracic Society(ATS) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) have adopted a new definition of pulmonary rehabilitation: “Pulmonary rehabilitation is a comprehensive intervention based on a thorough patient assessment followed by patient-tailored therapies that include, but are not limited to, exercise training, education, and behavior change, designed to improve the physical and psychological condition of people with chronic respiratory disease and to promote the long-term adherence to health-enhancing behaviors".45

As per the practice guidelines of the American College of Chest Physicians and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation (ACCP/AACVPR), "Any stable patient suffering from respiratory symptoms and having a chronic lung disease should consider pulmonary rehabilitation".46

Pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) may result in long-term bronchial and parenchymal structural abnormalities even with appropriate treatment, which results in decreased quality of life.

Minimizing symptom load, optimizing exercise performance, encouraging autonomy, raising involvement in daily activities, improving (health-related) quality of life, and bringing about long-term health-improving behavior change are among the objectives of pulmonary rehabilitation.

1. Frequency and duration of PR in PTB sequelae47

Pulmonary rehabilitation programme of 6–12 weeks are recommended.

Pulmonary rehabilitation regimens should include at least twice-weekly supervised sessions. A third session of specified exercise can be completed unsupervised.

2. Equipment required for PR

• Treadmill

• Stationary bicycle

• Access to stairs or step box

• Access to stairs or step box

• Arm crank ergometer

• Hand weights

• Resistive exercise bands

3. Components of PR

i. Breathing techniques

ii. Airway clearance techniques

iii. Exercise training

iv. Yoga

v. Education

vi. Psychological support

vii. Nutritional advice

1. Breathing techniques48

Pursed lip breathing:

It reduces shortness of breath and gives a quick and easy approach to slow down the rate of breathing, making each breath more effective.

When short of breath, pursed lip breathing helps to get more oxygen into the lungs and calms down and to have better breath control.

Technique:

• To sit down in a chair and relax the neck and shoulder muscles.

• Breathe in slowly through the nose, making sure to keep the mouth closed.

• " Pucker, or "purse" the lips as if going to whistle or gently blow out a candle.

• And then breathe out, or exhale, all of the air in the lungs through mouth slowly and gently through pursed lips.

• Try to breathe out longer than inhalation.